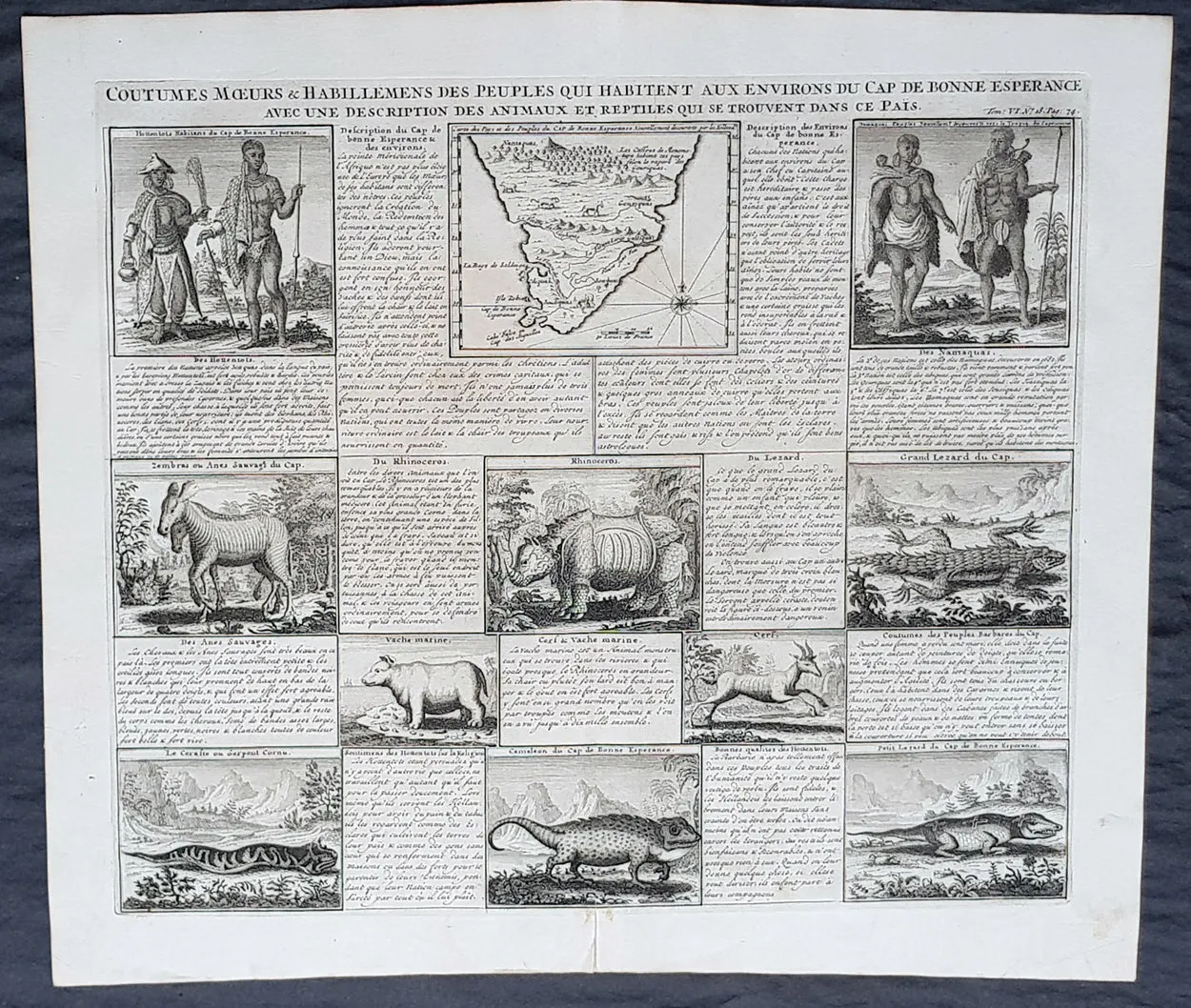

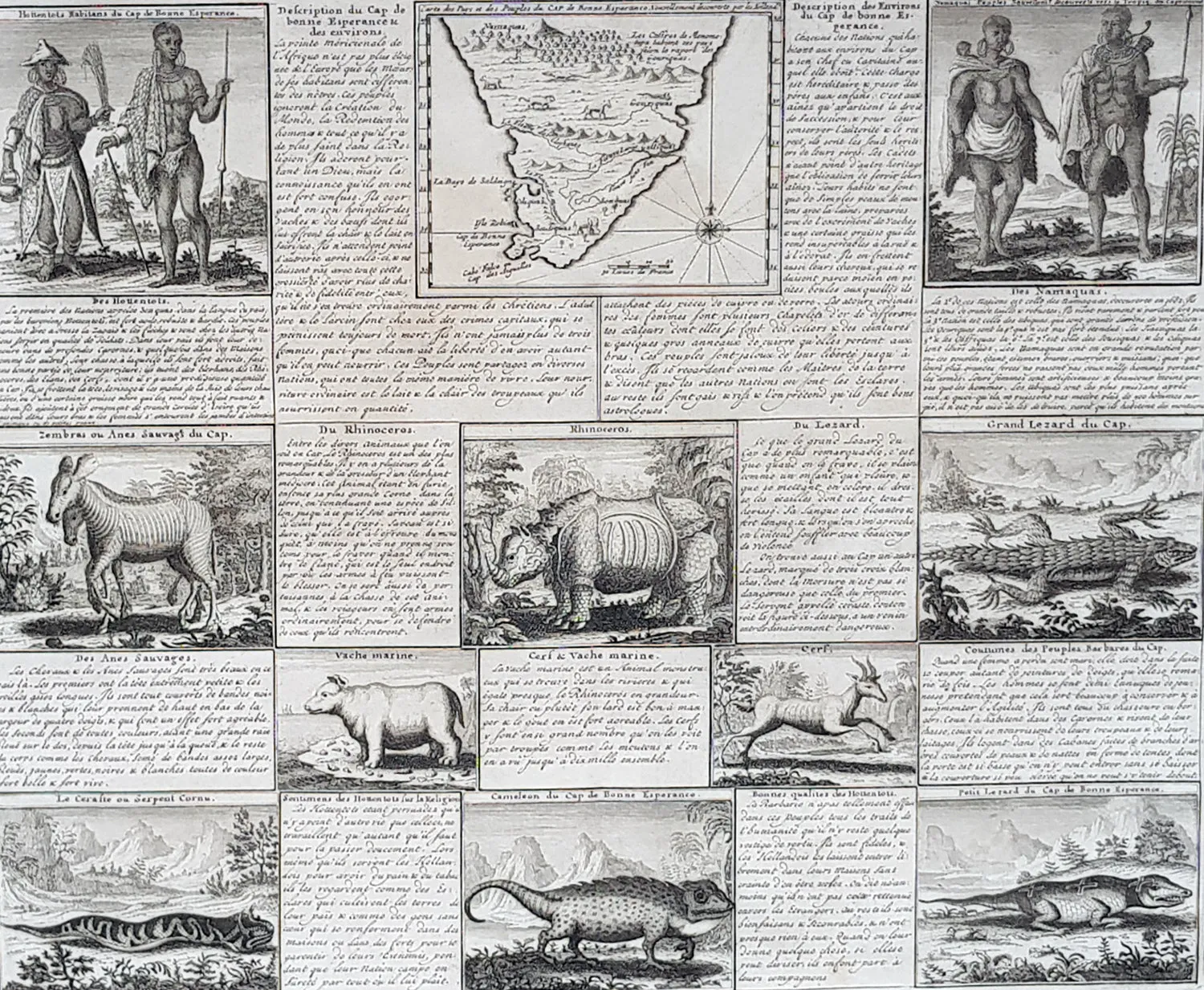

- Title : Coutumes Moeurs & Habillemens Des Peuples Qui Habitent Aux Environs du Cap de Bonne Esperance......

- Size: 20in x 17 1/2in (510mm x 440mm)

- Date : 1719

- Ref #: 50639

Description:

This large original copper-plate engraved antique map with views of The Cape of Good Hope, Southern Africa - with 10 vignettes of the peoples, animals & reptiles of the area - was published by Henri Abraham Chatelain in 1719, in his famous Atlas Historique.

These are truly some of the best early engravings of this region done at the time that were copied by the likes of Prevost, Harrison & others in the 18th century, but not with the same eye for detail.

General Definitions:

Paper thickness and quality: - Heavy and stable

Paper color : - off white

Age of map color: -

Colors used: -

General color appearance: -

Paper size: - 20in x 17 1/2in (510mm x 440mm)

Plate size: - 17 1/2in x 15in (440mm x 380mm)

Margins: - Min 1in (25mm)

Imperfections:

Margins: - None

Plate area: - None

Verso: - None

Background:

By the early 17th century, Portugals maritime power was starting to decline, and English and Dutch merchants competed to oust Lisbon from its lucrative monopoly on the spice trade. Representatives of the British East India Company did call sporadically at the Cape in search of provisions as early as 1601, but later came to favour Ascension Island and St. Helena as alternative ports of refuge. Dutch interest was aroused after 1647, when two employees of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) were shipwrecked there for several months. The sailors were able to survive by obtaining fresh water and meat from the natives. They also sowed vegetables in the fertile soil. Upon their return to Holland, they reported favourably on the Capes potential as a warehouse and garden for provisions to stock passing ships for long voyages.

In 1652, a century and a half after the discovery of the Cape sea route, Jan van Riebeeck established a victualling station at the Cape of Good Hope, at what would become Cape Town, on behalf of the Dutch East India Company. In time, the Cape became home to a large population of vrijlieden, also known as vrijburgers (lit. free citizens), former Company employees who stayed in Dutch territories overseas after serving their contracts. Dutch traders also imported thousands of slaves to the fledgling colony from Indonesia, Madagascar, and parts of eastern Africa. Some of the earliest mixed race communities in the country were formed through unions between vrijburgers, their slaves, and various indigenous peoples. This led to the development of a new ethnic group, the Cape Coloureds, most of whom adopted the Dutch language and Christian faith.

The eastward expansion of Dutch colonists ushered in a series of wars with the southwesterly migrating Xhosa tribe, known as the Xhosa Wars, as both sides competed for the pastureland necessary to graze their cattle near the Great Fish River. Vrijburgers who became independent farmers on the frontier were known as Boers, with some adopting semi-nomadic lifestyles being denoted as trekboers. The Boers formed loose militias, which they termed commandos, and forged alliances with Khoisan groups to repel Xhosa raids. Both sides launched bloody but inconclusive offensives, and sporadic violence, often accompanied by livestock theft, remained common for several decades.

Great Britain occupied Cape Town between 1795 and 1803 to prevent it from falling under the control of the French First Republic, which had invaded the Low Countries. Despite briefly returning to Dutch rule under the Batavian Republic in 1803, the Cape was occupied again by the British in 1806. Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, it was formally ceded to Great Britain and became an integral part of the British Empire. British emigration to South Africa began around 1818, subsequently culminating in the arrival of the 1820 Settlers. The new colonists were induced to settle for a variety of reasons, namely to increase the size of the European workforce and to bolster frontier regions against Xhosa incursions.

In the first two decades of the 19th century, the Zulu people grew in power and expanded their territory under their leader, Shaka. Shakas warfare indirectly led to the Mfecane (crushing), in which 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 people were killed and the inland plateau was devastated and depopulated in the early 1820s. An offshoot of the Zulu, the Matabele people created a larger empire that included large parts of the highveld under their king Mzilikazi.

During the early 1800s, many Dutch settlers departed from the Cape Colony, where they had been subjected to British control. They migrated to the future Natal, Orange Free State, and Transvaal regions. The Boers founded the Boer Republics: the South African Republic (now Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West provinces), the Natalia Republic (KwaZulu-Natal), and the Orange Free State (Free State).

The discovery of diamonds in 1867 and gold in 1884 in the interior started the Mineral Revolution and increased economic growth and immigration. This intensified British efforts to gain control over the indigenous peoples. The struggle to control these important economic resources was a factor in relations between Europeans and the indigenous population and also between the Boers and the British.

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following Lord Carnarvons successful introduction of federation in Canada, it was thought that similar political effort, coupled with military campaigns, might succeed with the African kingdoms, tribal areas and Boer republics in South Africa. In 1874, Sir Henry Bartle Frere was sent to South Africa as High Commissioner for the British Empire to bring such plans into being. Among the obstacles were the presence of the independent states of the Boers and the Kingdom of Zululand and its army. The Zulu nation defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana. Eventually, though, the war was lost, resulting in the termination of the Zulu nations independence.

The Boer Republics successfully resisted British encroachments during the First Boer War (1880–1881) using guerrilla warfare tactics, which were well suited to local conditions. The British returned with greater numbers, more experience, and new strategy in the Second Boer War (1899–1902) but suffered heavy casualties through attrition; nonetheless, they were ultimately successful.